Hollistic urban design: Enhancing Perceived Safeness in Torstorp

The problem:

How might we bridge the gap between factual safety and perceived safeness by rethinking how lighting, spatial design, and community identity can work together to make residents feel comfortable using public spaces after dark.

Every element in an urban space changes human behavior; true safety comes from designing those dynamics intentionally.

About

As part of the Holistic Design of Engineering Systems course at the Technical University of Denmark, our team collaborated with the Crime Prevention Team of Høje-Taastrup Municipality to address a paradox: while actual crime rates had fallen, residents in the Torstorp neighborhood reported feeling less safe.

My role

Conducted and facilitated resident and stakeholder interviews to understand perceptions of safety and nighttime behavior.

Documented and synthesized user data into actionable insights guiding design decisions.

Co-led the design and development of the final solution proposal, ensuring alignment between technical feasibility, social sensitivity, and stakeholder goals.

Acted as a bridge between research findings, user needs, and concept formulation throughout the project.

Solution

LightLink, a smart and context-aware lighting system designed to enhance perceived safeness in Torstorp.

Integrates light theory, Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) principles, and community-driven art projections to encourage voluntary nighttime activity.

Uses ambient and responsive lighting to reduce dark zones and light tunnels while fostering community identity and comfort.

Aims to balance technical, social, and environmental considerations rather than simply increasing brightness.

Result

Validated through resident testing and expert feedback, demonstrating strong potential to improve perceived safeness.

Positively received by the Crime Prevention Team, who expressed intent to scale and present the concept locally

Learnings

Urban design interventions are systemic; even small physical changes reshape social behaviors and perceptions.

Designing for safety requires anticipating both intended and unintended effects on community dynamics.

True improvement in perceived safeness comes from holistic, interdisciplinary design, not just technical fixes like more lighting.

Engaging users early and often is vital to ensure solutions resonate emotionally as well as functionally.

Staying at the office when trying to understand a problem never helps. The first order of business was to get out there and see things for ourselves. So here we are, walking around the project area with the head of the crime prevention team, trying to get a feel for what’s really going on.

We’ve made several excursions to the area to document the environment. Listening to experts is, of course, important, but it’s just as important to form your own opinions based on the discourses and gathered information, and how they relate to the reality on the ground. Being there in person helps bridge the gap between what is said and what is actually experienced.

And after dark, we could see for ourselves. As the image shows, there is a lot of dark space with nowhere for light to effectively reflect. The field of vision and movement is linear and bidirectional, creating a constrained and almost claustrophobic sensation. It is easy to understand why this environment might be perceived as unsafe.

Close by, there are these brick façades with beautiful brickwork and neat hedges.

However, after dark, these features take on another character. The façades look dark and impose a wall-like sensation over the pathway, while the greenery becomes barely visible, creating a very unsettling atmosphere.

In our selected pilot area within the neighbourhood, we documented all the characteristics that contribute to the feeling of being unsafe. This not only helps us understand the nature of the problem but also provides a baseline against which future improvements can be measured.

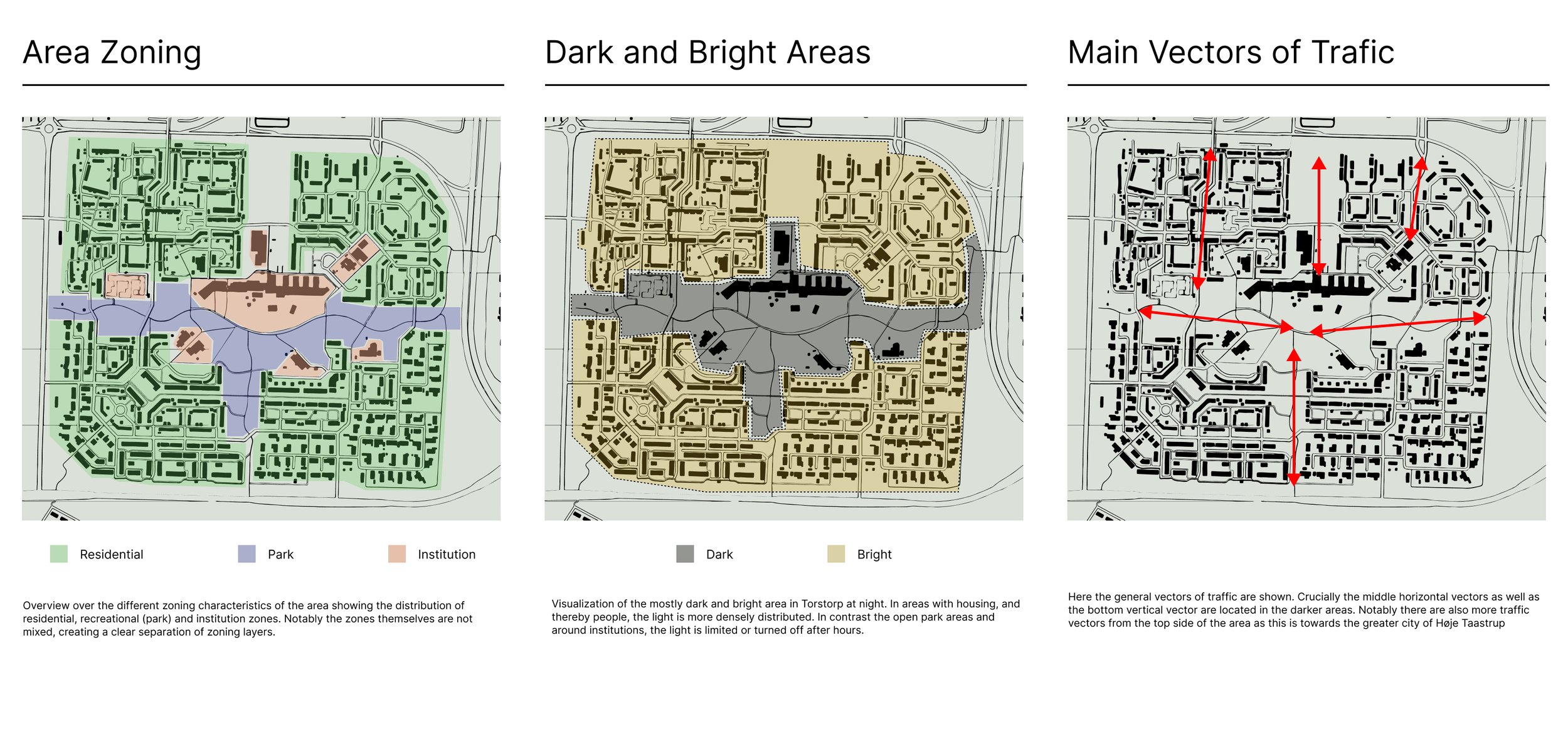

After the site visits, a bird’s-eye view helped us understand the zoning, lighting, and traffic patterns, providing a holistic picture of the pilot area in its wider context. We found that the area has few traffic routes and no through traffic, functioning almost like a peninsula with only one meaningful connection to the city. As a result, only residents tend to enter, reducing natural surveillance and the presence of capable guardians. Architecturally, the main pedestrian routes are set away from where people live and are poorly lit, further reinforcing a sense of isolation and unsafety.

Having developed a holistic understanding through conversations with experts, locals, and our own observations and interpretations, we were able to create concepts that address the identified problems in an integrated way.

After conceptualization, testing, iteration, and validation, we developed a master plan that holistically addresses both the social and infrastructural challenges within the local context. It focuses on enhancing the existing infrastructure by introducing lighting in strategic locations, not only to improve visibility but also to make it artistic and interactive. The plan also aims to engage the local community, encouraging people to spend more time outdoors, even in winter, and to attract visitors from the surrounding areas.